A New Art History

By Kelly Kristin Jones

Memories of visiting my grandmother’s bungalow mostly consist of sitting on her spongy wall-to-wall carpet paging through stacks of her art books.

Anneliese Keller Lott, my Oma, immigrated to the US when she was 19 with little more than a handbag. She worked her way up to Head of Circulation at a small, private university library on the east coast. Quite a feat for a woman with a heavy accent and no high school diploma.

Her boss at the university library, recognizing her as a fellow aesthete, let her adopt the art history books weeded from the shelves.

After retiring, Oma moved to a modest suburb of Chicago, with scores of boxes filled with her books. They smelled like history and were filled with art. She was proud of them. They represented more than just an education - they were placeholders for a kind of socio-economic status she didn’t think she could actually achieve. And her tiny living room overflowed with this unlikely second-hand collection.

Van Gogh! Picasso! Da Vinci! Rembrandt!

Most were oversized volumes with faded cloth covers - the book jackets long gone by the time they came into her possession. Some had tipped-in color plates and others had glossy pages full of reproductions, but all claimed to bear the work of “The Masters”.

Monet! Michelangelo! Vermeer! Munch!

After dinner, I would migrate to the living room floor, tuck my legs under the coffee table, and look through her precious stamped and debugged books. Carefully. I wasn’t allowed to let my dessert come near the pages. So I would scoot back-and-forth, table to table, until I had my fill of either painter or pie.

Dali! Klimt! Raphael! Renoir!

For centuries, women have been systematically excluded from the art historical record. This was due to a number of factors: art forms like textiles and the “decorative arts” were often dismissed as craft and not “fine art”; many women were kept from pursuing higher education, let alone fine arts training; and, perhaps most significantly, men controlled the practice, theory and documentation of the discipline.

Botticelli! Pollock! Cezanne! Valazquez!

My mother recently told me that she had wanted to be an artist. She always decorates my birthday cards with tiny sketches, and forever finds quiet ways to make her mark, but I never knew she dreamt of pursuing art professionally. As a first-generation college graduate from a working class immigrant family, she felt too much familial pressure to make such a risky career choice. She also says she lacked the confidence. She didn’t know any female artists, rarely saw any in the museums she visited in New York City on the weekends, and didn’t find any in the books her mother, my Oma, collected. Is it any wonder that she shied away?

Manet! Rubens! Whistler! Caravaggio!

When I walked into my first undergraduate Art History class in 2004, only 26 female artists were included in my McGraw-Hill textbook. Twenty-one of them were simply listed in a “Women in Art” side blurb. Only 4 were women of color, all quilters and all deemed “crafters” and “outsider artists”. In 685 pages, this was all ‘official’ Art History could offer.

Warhol! Degas! Matisse! Seurat!

Since I’m the “Artist” in the family, Oma gave me most of her art books when she moved into an assisted care home. It wasn’t until isolation that I delved into them again. Inside I found pages of genius white male artists, with careers reinterpreted by a famous white male art historian, all held in institutions, led by white men, in states run by white men, in a country run, predominantly, by white men.

Magritte! Wood! Gauguin! Hopper!

The traditional art-historical narrative, maintained by practices of marginalization, omission, and erasure, is due for a reckoning. And yes, things are changing. But with only 27 women (out of 318 artists) included in the 2010 edition of H.W. Janson’s survey, Basic History of Western Art - up from zero in the late 1980’s - we have a long way to go.

Van Eyck! Goya! Rivera! Delacroix! Titian!

We make up half the world (and 60% of fine arts degrees). But as I page through my grandmother’s books on my own living room floor, with my daughter in my arms, you’d never know it.

***

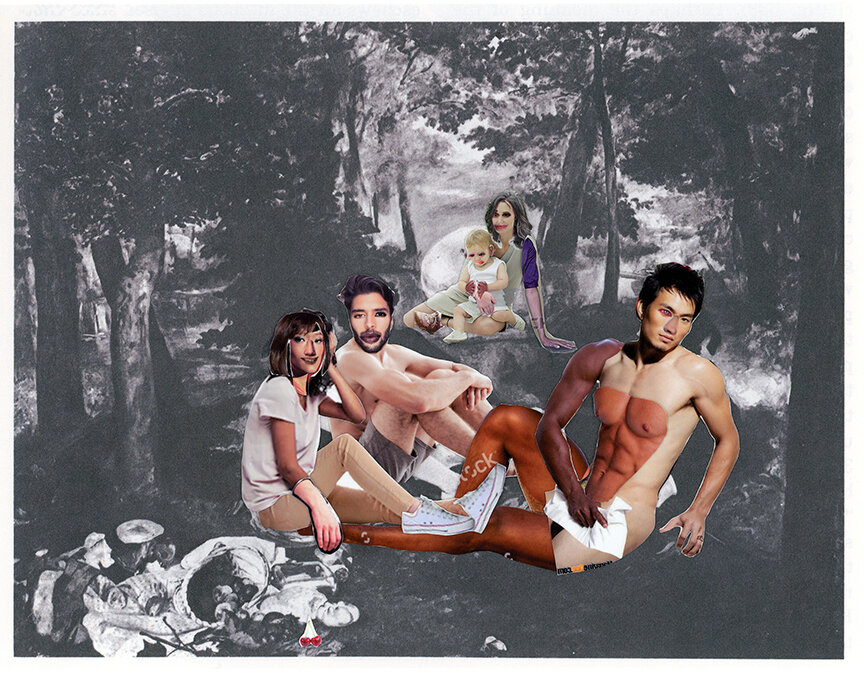

I address these omissions with cut paper and glue. My collected photographs of female artists - some famous, many not - placed on top of the bodies of men, craft a new version of the past and vision for the present. I’m less interested in accessing a denied truth; rather, I want to create strange and mythical characters that simultaneously embody the role of artist, model and hero.

It’s a playful but tedious process.

That connection between tedium and reproduction is most often found in the feminized “arts and crafts” tradition, and kept separate from the realm of high art. Crafts are characterized by their tedious attributes: they are monotonous, repetitive, and time-consuming. They also contain the feminized aspects of reproduction: designated at home, practiced by women, and often worked from patterns rather than original design. While often subversively embedded with an individual female artist’s, marks, symbols, and culture.

The most strident and visible expressions of subversive craft involve the practice of “yarn-bombing,” or wrapping public objects in boisterous knitting. A historical - and persistent - tendency to associate craft with softness, delicacy, and obedience, provides a useful foil for more irreverent elements. Such craftswomen have been known to face fines, or even arrests, for their work. Each time I leave my home to cover a monument in collage, I am confronted by at least one white male passerby wanting to know what I’m doing and why. With our president’s newest Executive Order on “Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes” I can be imprisoned for up to 10 years. The work that I’ve engaged in since 2017 has become criminal.

One day, when my daughter looks through my grandmother’s art history books, she’ll see my collages. Positioned at the tender intersection of fine art and craft, my paper works are as destabilizing as they are ridiculous. Made at home, they betray the thing my Oma valued most. Considering they are made to offer her great-granddaughter a new canon, I think she’d understand.

* The italicized artist names throughout the essay are the results of my Google search for “most famous painters”. Frida Kahlo, at #34, was the first woman on the list. Her husband, Diego Rivera, was listed at #31.